ArtSeen

GARRY WINOGRAND

“I think there isn’t a photograph in the world that has any narrative ability,” Garry Winogrand told Bill Moyers in 1982. “They do not tell stories—they show you what something looks like. To a camera.” In interview after interview, the photographer clearly stated his belief in the limited capacity of the medium. Yet some of the most poignant images he left behind, many of which are currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, challenge his words. The clothes and cars may mark the pictures as outdated, but the images speak of a relationship to photography that continues to haunt our looking.

On View

The Metropolitan Museum Of ArtJune 27 – September 21, 2014

New York

Winogrand was a full-time flâneur, wandering the streets of midtown Manhattan (and later the country), exposing over 26,000 rolls of film before his untimely death in 1984. A self proclaimed “student of America,” his quest for the nature of American identity informed each and every photograph he took. Aside from a few political rallies, rarely did his work focus on powerful figures or celebrities. Instead he remained one step removed, feet planted in the crowd, his photographs nearly always overflowing with bodies, architecture, and other man-made accessories. He was always “throwing more film at the world,” Leo Rubinfien, guest curator of the exhibition, writes in his luminous catalogue essay. Fur-clad women rush down Madison Avenue with shopping bags; a couple in bell-bottoms smokes cigarettes in Central Park; another couple, one dressed in uniform, waits for a plane to Southeast Asia; a toddler plays in the arid driveway of a desert suburb; riots storm through dirty city streets. Winogrand was after the ripples of historical change, rather than the decisive moment.

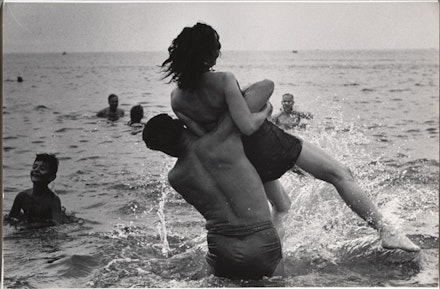

Born and raised in the Bronx, Winogrand developed his photographic eye in the 1950s when the American magazine (Life, Time, Look, Sports Illustrated, and others) cultivated a highly specific visual culture of moral heroism and technological triumph. Photographers were respected as the magazine’s leading assets, but the position came with the specific expectation to adhere to the narrative of post-war American exceptionalism: America was the greatest nation on earth, and it was a fact best told in pictures. Winogrand began his professional life in this climate, evidenced by his single contribution to Edward Steichen’s influential 1955 exhibition Family of Man, in which a couple leisurely frolics in the Coney Island surf.

Less than a decade later, the medium’s practitioners would begin to reject the role of hegemonic storyteller. Winogrand and his colleagues, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Tod Papageorge, began to formally exploit the medium’s weaknesses in a push towards greater “authenticity.” Though Winogrand revered his predecessors like Walker Evans, and strove to emulate Robert Frank’s The Americans, he often expressed doubt in the photograph’s abilities to dictate change. In interviews he would dodge any impositions that his work commented upon the “human condition,” instead choosing to define a photograph strictly as “an illusion of a literal description.”

This approach to making images—using the visual language of photography to question the veracity of the medium’s moralistic claims—would become more explicit in his work as the years passed. One photograph from 1968 shows an older African-American man, dressed in a wool coat and extending his hand to receive something hidden. A closed, white fist enters from outside the frame; we cannot see what the hand offers. Winogrand must have been aware of the insinuated, potentially problematic narrative, but also understood that the power of this image lies in its ambiguity. We know nothing of the story of these two men’s acquaintance; we know only what is recorded when the shutter let in a brief glimpse of light. To assume this photograph holds a complete story within it, Winogrand would argue, is presumptuous at best, and immoral at worst.

An earlier photograph, taken outside the Air Force Academy of Colorado Springs in 1964, pushes this notion of narrative fragmentation even further. The image shows a group of people, both retired military officers and civilians, gathered around the entrance to a city building. In the center of the photograph, a veteran who has lost both his legs supports himself with his arms on the sidewalk. He is without a wheelchair, and so the vertical disparity between bodies is staggering. Not a single person in the photograph looks down to make eye contact with the veteran—only the photographer looks. This image highlights the visceral difference between what a photograph actually shows, and the narrative one reads into the image. Almost instinctually, we fill in the before and after. We accuse those in the photograph of neglect, or feel accused ourselves. This connection between story and picture must be centuries old —it surely goes back further than Life and Time—but in images like these, Winogrand exploits the automated leap to the fullest extent.

This intrinsic desire for story, for a beginning, middle, and end, extends to the structure of the exhibition itself. A substantial portion of the prints on view at the Metropolitan (the entire last room) are each classified as a “posthumous digital reproduction from original negative.” Throughout his last decade, Winogrand continued his prolific habits on the street, yet neglected to develop the resulting photographs. Editing was seemingly of little interest to him, a pattern begun earlier in his career when he allowed his peers to compose his photo books. It was the act of photography—the hunt—that drove his creativity. At the time of his death, Winogrand left 2,500 rolls of undeveloped film and 4,100 unedited contact sheets, all without specific instructions, to the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona. Unedited and largely unseen by the artist himself, Rubinfien and the other curators reviewed the thousands of contact sheets, and selected less than one hundred images to develop posthumously. Almost all of the images dated after 1978 were culled from the archives in this way.

The organizers’ anxiety around this decision is palpable. In the final room of the exhibition, a looping video shows Winogrand—his boots crossed on a table in front, arms leisurely bowed behind his head—dismissing notions of specific intention within a single image, in his characteristically acidic and witty style. “Its not all that serious,” he says, “I do it and I close the door on it.”

One of the last “posthumous digital reproductions” shows a body flat against the asphalt as a Porsche speeds out of the frame. The image is blurred, but it looks to be a woman struck, perhaps fatally, by a car. The photograph is dated to 1983, the year of Winogrand’s diagnosis with aggressive terminal cancer. And so despite the fact that he likely never saw this image on paper, the link between image and maker is locked into place. Should the curators, who selected this image for print from among the thousands, be chastised for attempting to find a contemplative ending to a life cut short? The alternatives, of showing nothing or everything, feel equally unwieldy, and so the controversy continues. Winogrand may have believed that photographs didn’t tell complete stories in themselves, but he didn’t account for the stories that arise from our looking.