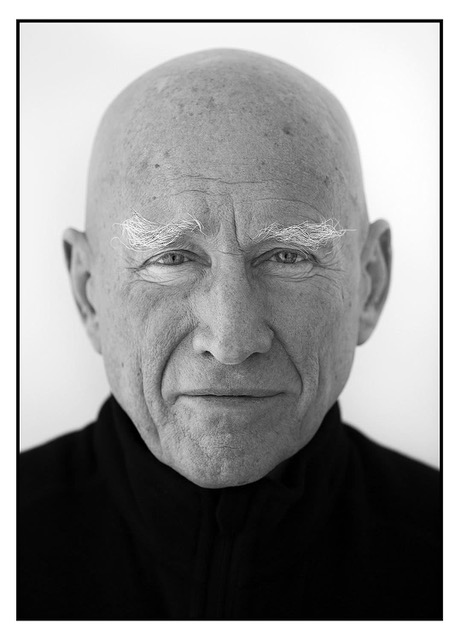

September 12, 2021Calling a photographic series epic might sound like hype, but if anything it understates the latest project of Sebastião Salgado. The Paris-based Brazilian photographer spent seven years in the Amazon, working in treacherous conditions to document the single most important source of water, biodiversity and natural resources in the world, a vast and lush rain forest with large areas never seen by humans. That the region is under threat, with possibly catastrophic consequences for the planet, adds urgency to Salgado’s efforts.

With his wife, Léila Wanick Salgado, serving as his editor, graphic designer and frequent companion, Salgado has turned the photographic fruits of his work into one of the definitive documents of both man and nature in the form of a TASCHEN SUMO book, Amazônia, as well as an exhibition at Peter Fetterman Gallery in Los Angeles.

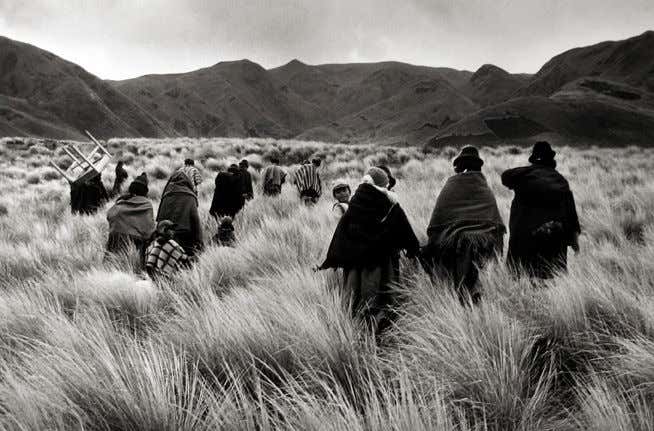

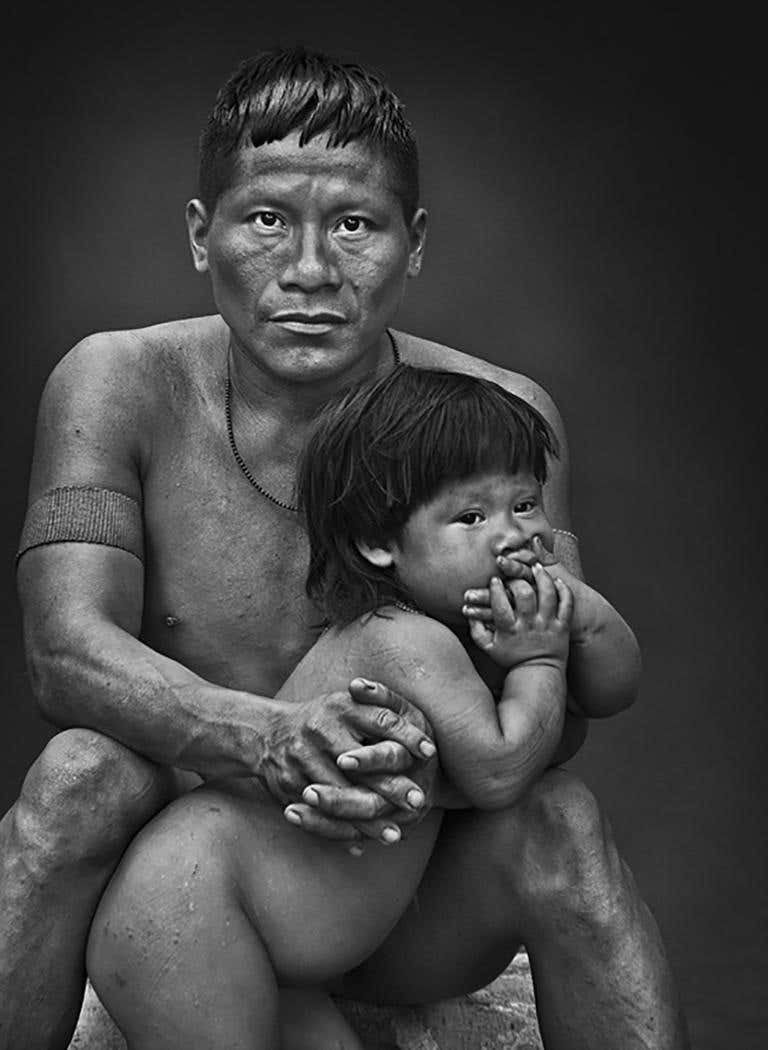

The black-and white images are intense, lustrous and rich, valuable not only for their subjects — including indigenous peoples, presented in portraits of poignant dignity — but also as artworks and examples of how good photography can be.

Based on the many thousands of pictures he took, the tome comes in a hardcover version plus a Collector’s Edition, accompanied by a separate clothbound caption book and a book stand designed by the architect RENZO PIANO, as well as four Art Editions, each with the book stand and a signed print and limited to 100 copies.

Fetterman, a close friend of Salgado’s for decades, hand selected his favorite images, many of which don’t appear in the book, for his gallery show, adding photos from previous series to create a 70-work exhibition (on view through October 15). “Sebastião is a force of nature,” says Fetterman. “He’s an epic image maker on a grand scale. He’s a cross between Ansel Adams and Edward Curtis.”

Fetterman’s favorite photographs are the “purely humanistic ones,” he says. “There’s one image in Amazônia of a young woman with a makeup mirror — it’s like a Rembrandt.” He notes that Salgado uses the proceeds from the print and books sales to fund future expeditions and his tree-planting and -cultivation nonprofit, Instituto Terra, based in Brazil’s Minas Gerais.

Introspective talked with Salgado, 77, when he recently returned to Paris after a much-needed vacation.

This project is monumental. How did it come about?

I started to travel to Amazônia, and each time, it felt a little bit more degraded. I saw that it was necessary for me to go back to this endangered ecosystem, where there is a lot of destruction and where the Indians are having a very hard moment.

Right after my Genesis project [a 2013 series depicting untouched lands, animals and cultures] was completed, I flew from the exhibition in Rio de Janeiro to Amazônia to start photographing. And I shot until the end of 2019. I worked for close to seven years in Amazônia. I took my whole life there.

How do you fund your work? It looks elaborate and expensive.

The sale of my prints finances it. All the money that comes from photography, I put back in photography. It’s expensive because to go to the Indian community, it is necessary for me to organize an expedition and get authorization — a majority of these tribes you can reach only by boat. And the [Brazilian government’s] National Indian Foundation has to give authorization for you to go.

You have to buy food for three or four months in advance. I had to have one translator, one anthropologist, one guy from the National Indian Foundation and a bush captain who knows how to fish in the waters of Amazônia and knows how to set up an encampment. In the end, we were about twelve to eighteen people on each trip.

Was it dangerous?

No, no, no. Well, there is some danger. The jungle, it’s very soft, it’s very beautiful, it’s very nice to be there. You even sleep very well in hammocks. But you can’t sleep on the ground in Amazônia because there are snakes and scorpions. The big danger is the feral hogs. A thousand of them can come together, and they can eat you. And when they come, we must get a place to climb.

OK, this sounds very dangerous.

The other thing that is sometimes dangerous: You must pay attention when you wash yourself in the river. You cannot do it past five or six in the evening, when it becomes dark, because the big snakes live in the rivers — constrictors that are ten meters long. They go to get food. And if they get you, they break all your bones. They constrict you and eat you.

This keeps getting worse.

It’s only a danger if you don’t know how to handle it. You see, you must pay attention. It’s like an Indian who comes to New York. It’s a disaster, because they don’t know how to cross a street and a car can kill them. And for them, it’s more dangerous to go to New York than for you to go to the jungle. All danger is relative.

What kind of camera and film do you use for these trips?

I used to work with film. And all the work that I shot after 2013 is all digital, all shot with Canon’s 1DS. I had Canon develop this camera specially for me, though, for the trip. In Amazônia, you must have a camera that resists the humidity, because sometimes you have one hundred percent humidity.

Why did you shoot Amazônia in black and white?

I shoot everything in black and white, I don’t shoot in color. When I started photography, I worked for many years for the Gamma and Magnum agencies, and they were all color assignments. But color, for me, was disturbing, because the colors became too important, much more important than the reality [of the scene]. A distraction.

Getting past the distraction, I could concentrate on what was necessary. Of course, nothing is really black-and-white, black-and-white is an abstraction. It’s all grays.

There are wonderful shots from airplanes. Is it true to say that some are vistas few people have seen?

Exactly. For example, the pictures you know from Amazônia show a flat land with rivers and a lake in the middle. But there’s a chain of mountains in Brazil that no one knows — and I wanted to see them.

The small planes can’t go there, since there is nowhere to refuel. I asked Brazilian authorities to help. So, I went with the Brazilian army on many missions. They allowed me to fly in helicopters with an open door.

What was it like photographing the indigenous peoples?

There are about one hundred ninety tribes in Amazônia, with more than a hundred sixty different languages. For each trip, it was necessary to organize a different translator, a different anthropologist.

The communities are very nice, they are very delicate people. Once you are there, you are part of the community, they are very happy that you are there. Some became my friends forever.

You’ve done so much photography about the environment, this seems like the perfect capstone for you.

Photography is a way of life. I don’t do it because I’m a reporter or an anthropologist. I take pictures of the things that I love. If I was not in love with the Amazônia, I wouldn’t want to spend seven years in Amazônia sleeping in the bush, eating not very well and being far away from city comforts.

When I photographed Genesis, it was the same thing. I was in love with my planet. When I photographed the starvation in Africa, I was so upset about the state of health in the world. I did Amazônia because I love it, I love the Indians. And I believe we must have a better planet, and we must protect nature.