Open: Mon-Sat 10am-6pm

Visit

Laurent Grasso: ANIMA

Perrotin Seoul, Seoul

Thu 4 May 2023 to Sat 17 Jun 2023

10 Dosan-daero 45-gil, Gangnam-gu, Laurent Grasso: ANIMA

Mon-Sat 10am-6pm

Artist: Laurent Grasso

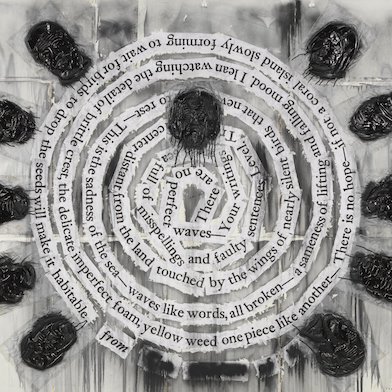

Perrotin Seoul presents ANIMA, Laurent Grasso’s second solo exhibition with the gallery in Korea. After Perrotin Seoul’s inaugural exhibition at Samcheong in 2016, the French artist comes back with a large selection of paintings, sculptures, and neon works as well as Anima (2022), a new film which had its world premiere in Paris in the fall of last year.

In the exhibition, Laurent Grasso explores the visible and the invisible, creating bridges beyond the boundaries between human and non-human. Avoiding the pitfalls of representation and anthropomorphism, through his paintings, film, and sculptures, he aims to fulfill our world with new hypotheses.

Grasso’s work is inspired by scientific discoveries and human sciences, as well as by beliefs and mythologies attached to specific phenomena or places. The artist conceived this exhibition ANIMA as a complete narrative with chapters like a film, a core medium in his artmaking, employing overhead camera shoots and various technologies and instruments to reveal things invisible to the human eye. Central to this exhibition, the film Anima (2022) is the fruit of a fertile exchange between art and scientific research begun several years ago in collaboration with Grégory Quenet, an environmental historian, and in the footsteps of the work of the philosopher Bruno Latour.

For this project, the artist is particularly interested in the spectacle behind the Mont Sainte-Odile, a place with a mysterious and telluric force, dominating the Plain of Alsace in France. This pilgrimage site is linked to the miracle of Saint Odile, and where perpetual adoration has been practiced since the end of the 19th century, is very close to a geoscientific survey point related to the study of the “Critical Zones” as described by Latour. But it is also a region traversed by powerful cosmo-telluric currents, which have attracted the interest of geobiologists, especially the stone fortifications better known as the “Pagan Wall,” stretching out over nearly 11 kilometers in the forest that encircles the mountain and remains an archaeological enigma.

Intrigued by the confluence of geological, mythological, and spiritual forces, Grasso researched the history of the area in collaboration with Quenet. Shot in Mont Sainte-Odile, the film mixes the perspectives and points of view of different protagonists — a man, a fox, rocks — populating a mysterious world that hovers in between reality and dreams with mystical elements such as suspended flames, ghostly clouds, and even a ‘pyrophone’, a 19th-century musical instrument that produces notes with mini explosions taking place inside a sequence of glass tubes. Choreographed camera movements, illusory transparent images made with a LIDAR scanner, ethereal lighting, and an esoteric soundtrack by Warren Ellis plunge spectators into a mysterious atmosphere where the invisible part of the world becomes visible. The idea is to detach oneself from human vision to ultimately create a new point of view. The artist revels in the idea that a tree, an animal, or a rock could have, in the film, an interiority of their own, like an unknown form of intelligence.

The multiplicity of perspectives adopted by the camera in the film finds a counterpart in the recurring motif of eyes that appear on bronze and neon Panoptes (2022) branches displayed in the entrance of the exhibition. They are reminiscent of the portrayals of Saint Odile who is often depicted holding her eyes on an open book. Eyes are a subject Grasso has already pursued for several projects. The symbol of the eye is found all over the monastery dedicated to Sainte Odile since it was founded to celebrate the miraculous recovery of her sight.

Grasso gives the trees a form of sensitivity by putting eyes on their branches and suggests the notion of an intelligence belonging to the plant world. Exploring the thresholds between the material and the immaterial, the artist transposes the materiality of the bronze of the Panoptes sculpture into a neon gas emitting light. Evoking the flow that passes through plants during photosynthesis, the neon Panoptes (2022) reflects a state of consciousness diffusing itself in the materiality of the world, presenting a conceptual juxtaposition.

Next to the Panoptes (2022), another work echoes an imagery raised by the film: the sculpture Anima (2023) depicts a young boy holding a fox. Directly inspired by the appearance of the same animal in the eponymous film, this work is part of a series that explores the child’s connection to the sacred. Like a messenger or an oracle, the young boy gives the impression that he has access to something unique or holds the key to knowledge. The fox, which appears several times in the film, seems to have transfigured through the screen to be embodied as a sculpture, provoking a sense of déjà vu and the back-and-forth shift between the world generated by the film and the exhibition space.

In the first-floor gallery, centered with The Helmet of Minerva (2023), a monumental onyx sculpture emanating a mysterious light, Grasso introduces a new series of paintings to complement his Studies into the Past that he began in 2009. This vast conceptual project incorporating elements from his film in paintings executed in the manner of the Renaissance masters focuses on the strange phenomena frequently rendered in his work such as clouds and flames. They seem to have transformed from the screen to fill the huge, vaulted architecture or the Mont Sainte-Odile depicted in the paintings. These pieces are fabricated in a quasi-scientific manner and the faithfully reproduced mythological, religious, and historic settings are interrupted by foreign objects and phenomena to upend our perception of the past. Grasso enjoys considering time as an artistic material, mixing temporalities, and developing projects around the concept of time travel. In fact, Grasso collaborates with conservationists to create these historical paintings to achieve what he calls a “false historical memory.” This creates a kind of archaeology of the future that disrupts the understanding of where they came from and when they were made.

Finally, the Future Herbarium series presents species of flowers, such as daisies, anemones, and other Asteraceae showing signs of mutation that could potentially occur in the near future. In this hypothetical world where the living would have taken new paths, the heart of the flowers has split, as though their DNA had undergone unusual modifications. The translucent materiality of his works refers to the imagery of the LIDAR scanners, which has the particularity of revealing realities invisible to the naked eye which we find in the film Anima (2022). The real is probed by means of scientific instruments to uncover potentialities that are only waiting to grow. In this respect, Future Herbarium can be seen as an outgrowth of Anima (2022), an unfolding of the energies latent in the film. The reflective surface of the palladium sheets on which the flowers are painted, and on which is reflected in an altered way in the video projection, accentuates the dialogue and discourse among the film, the paintings, and potential worlds.

Consequently, through the film Anima (2022), the viewer is faced with a territory that borders between reality and dream, and the edges of an unidentified world. Surreal and ambiguous, yet not entirely out of the realm of possibility, Grasso’s installation intuitively blends the past, present and future inevitably forcing visitors to question what they thought they knew.