Horses were

targeted

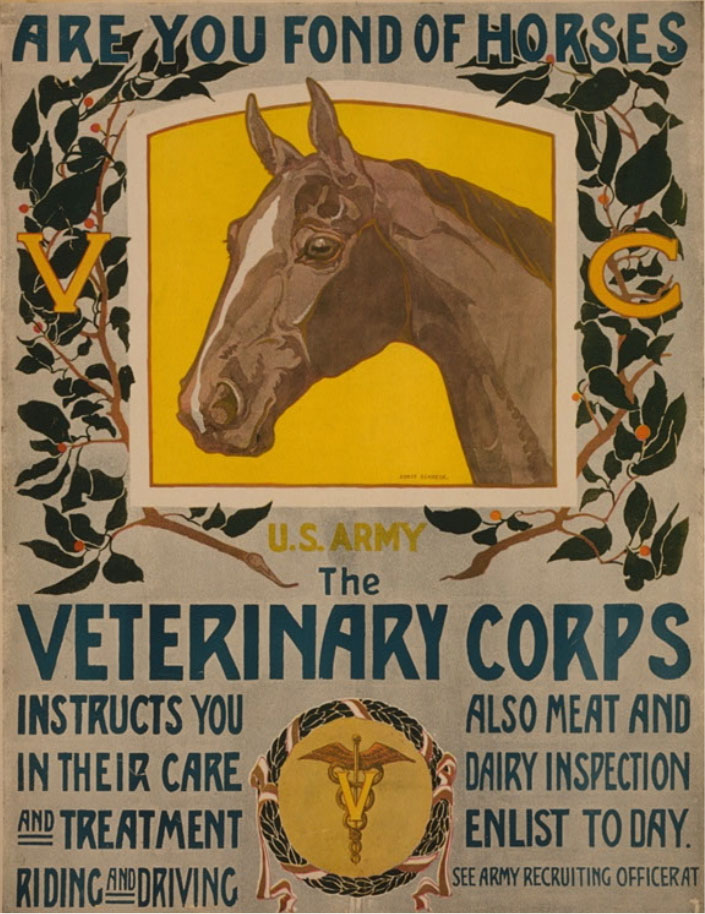

in one deadly German operation. Throughout the war, the United States supplied millions of horses and mules to Allied armies, the animals vital to transporting guns, equipment, and supplies across expansive battlefields. As with munitions shipments, German intelligence plotted against this commodity at its source.

At the suggestion of German spymaster Franz von Rintelen, Germany’s military intelligence service, the Abteilung IIIb, recruited a young American doctor, Anton Dilger, to carry out this unique mission. Dilger was born in 1884 on a farm in Front Royal, Virginia. His parents were German immigrants, and his father was awarded the Medal of Honor as a Union Army cavalry officer during the Civil War. The farm where Dilger grew up was later incorporated into the U.S. Army Front Royal Remount Station, ironically used to breed and train horses shipped overseas during World War I.

Dilger was sent to Germany to complete his education and, in 1908, earned a medical degree specializing in bacterial infections in animals. Early in the war, Dilger served as a volunteer surgeon at a German field hospital, where he witnessed horrors of war that shifted his allegiance to his father’s native country. He became a coveted recruit of German intelligence and returned to America in 1915 with mission in hand, as well as four vials of anthrax and a microbe known to cause glanders, a contagious disease deadly to horses and mules.

From a house in the Chevy Chase neighborhood of Washington, D.C., just five miles from the White House, Dilger assembled his laboratory for engineering a lethal biological weapon. Together with his brother Carl, who had operated a beer brewery in Montana and knew about the fermentation process, Dilger cultivated biological cultures in the basement lab. The anthrax and glanders cultures were then supplied to Frederick Hinsch, captain of an interned German ship who was an Abteilung IIIb operative in Baltimore. It was Hinsch who recruited pro-German dockhands and longshoremen to infect the horses and mules while they were in corrals in the East Coast ports awaiting shipment.

It was a deadly effective operation. From late 1915 and well into 1916, thousands of horses and mules were killed by the biological agents. There were human victims as well, including at least four individuals killed while working near the animal corrals during the winter of 1915.

Dilger returned to Germany in early 1916 and was later awarded the Iron Cross for his efforts. In 1917, the Abteilung IIIb assigned Dilger to Mexico, where he was to oversee sabotage operations against targets in the United States. He was also ordered to encourage Mexican officials to attack the United States, with the aim of keeping the U.S. Army occupied on the southwestern border. His efforts were largely unsuccessful, and Dilger left the country in 1918. In a twist of irony, Dilger traveled to Madrid, Spain during the height of the global influenza pandemic, where the biological weapons pioneer was infected by the lethal contagion. He died that year at the young age of thirty-four. Dilger’s full role in the biological attacks was not known until years later when it was discovered by the Mixed Claims Commission during an investigation into German wartime sabotage activities.

By December 1915, senior American officials had learned of the biological attacks and confronted the German Ambassador, Johann von Bernstorff, about it. Though von Bernstorff flatly denied involvement in any such activities, he ordered operatives in the United States to cease all biological attacks, alarmed the Americans might discover Germany’s true role.