Pity the poor human brain. People have misunderstood it for thousands of years. Ancient Egyptians thought it was a useless organ and tugged it out of dead pharaohs through the nose. Aristotle thought the brain was a cooling unit for the heart. Philosophers in the Middle Ages believed that certain brain cavities full of spinal fluid housed the human soul.

You’d think we’d know better nowadays, given that neuroscientists can peer inside a human skull to observe a living, functioning brain. Sadly, we still have fairy tales mixed in with the facts. For example, Ben Carson, the U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development and a former neurosurgeon, made a bit of a gaffe last month when he called the human brain a perfect storehouse of life's memories. Just electrify the right neurons, he claimed, and anyone can recite “verbatim, a book they read 60 years ago.” This is a fiction that scientists debunked decades ago. The brain is not a video recorder. Memories are distributed throughout your brain in bits and pieces, biased by your beliefs and feelings, and assembled in the moment.

Three brain myths, in particular, are repeated on an almost daily basis in news stories around the world. Let’s consider them one by one in the hopes that we can finally squash them.

The first myth is that the hormone cortisol causes stress. In March 2017 alone, I counted over 250 stories on Google News that call cortisol the “stress hormone.” (And that’s just in English.) But it’s simply not true. Cortisol’s main purpose is to provide a quick burst of energy when you need one. Your brain produces a cortisol surge every morning when you wake up, for example, and anytime you exert yourself. You constantly have cortisol in your bloodstream, and your brain regulates the amount throughout the day to help keep you alive and healthy.

Calling cortisol a “stress hormone” is like calling cake a “birthday food.” Sure, we serve cake at birthday parties, but far more cake is consumed in other circumstances: for dessert, snacks, weddings, anniversaries, even breakfast. Along the same lines, your brain spikes your cortisol level in many situations that are not stressful. It’s even conceivable that you can feel stress without a surge of cortisol, just like you can have a birthday without cake.

The second big myth, found in a mere 63 news stories in March, is that a region of the brain called the amygdala is responsible for creating fear, or for creating emotions more generally. This notion dates back to the 1930s when some scientists removed the amygdalae of rhesus monkeys, who then behaved in ways that seemed to show they were fearless (the monkeys, not the scientists). Ever since, the amygdala has been called the brain’s fear circuit, fear center, fear detector, fear processor, and dozens of similar names.

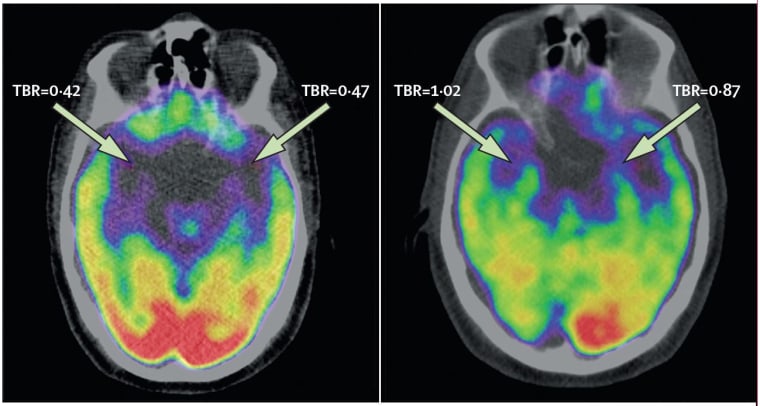

Nevertheless, more recent research has obliterated any necessary connection between the amygdala and emotion. Your amygdala increases in activity during a wide range of mental phenomena, including thinking, remembering the past, imagining the future, feeling uncertainty, eating, drinking, smelling, feeling pain, using language, receiving rewards, having social interactions, and regulating your body’s internal systems. Oh yes, and emotion too, sometimes. This laundry list is supported by thousands of brain-imaging experiments involving tens of thousands of test subjects.

In addition, scientists have studied fear in people who lack a functioning amygdala. A famous case involves a set of identical twins with identical amygdala damage. One twin has difficulties related to fear, but the other experiences and perceives fear completely normally. Overall, the amygdala may be important for emotion (and dozens of other phenomena), but it is neither necessary nor sufficient for emotion.

Current scientific thinking is that the amygdala helps the brain deal with uncertainty or ambiguity. When you’re in a novel or unfamiliar situation, the amygdala helps to link that situation to basic circuits for survival behaviors like fleeing or fighting. Fear, however, is a much more complex mental phenomenon that is created by multiple brain networks working together.

It’s understandable that this myth about the amygdala has such staying power. We desperately want to know what makes us tick. Simple stories about the brain, like saying particular neurons are “for” fear or emotion, are attractive if they help to explain human nature. Ultimately, though, the only thing the brain is “for” is regulating your body’s energy balance so you stay alive. This means you can’t understand the complexities of the human mind by simply studying neurons. That’s like trying to understand jazz by studying vocal cords. Even if you cataloged every cell and measured every vibration, you still wouldn’t explain why Ella Fitzgerald makes us smile and weep.

Related: This Revolutionary Gene-Editing Tool Could Change the World

The last big myth is that areas of your brain “light up” or suddenly become active in response to events in the world. This is an incorrect view of brain activity that dates back to a 1952 study of — I’m not making this up — a piece of a brain cell from a dead giant squid. No human brain cell is ever dormant or switched off. Your whole brain is active all the time. Particular neurons may fire at faster and slower rates, but they’re always in a flurry of activity, dashing off thousands of predictions of what you might encounter next and preparing your body to deal with it. This constant storm of predictions, which scientists call intrinsic brain activity, ultimately produces everything you think, feel, or perceive.

The story of the switched-off brain is related to the biggest brain whopper of the 20th century, that humans use only 10 percent of their brain capacity. Fortunately, that myth is mostly dead now, except in Hollywood, which keeps churning out sci-fi movies like "Lucy" (2014) and "Limitless" (2011) based on this tired premise.

Our three myths together represent an outdated way to understand the brain, which is based on the question “where.” Where is stress produced? Where does fear live? Where is the brain activating? Such questions assume that stress, fear, and other psychological functions are found in distinct locations in the brain. We now know, however, that the brain is not a collection of independent mental organs, but a complex system of networks that form trillions of neural patterns.

Related: Algorithms Learn From Us, and We Can Be Better Teachers

As a result, neuroscientists are now exploring “how” questions: How does the brain create stress and fear? How does the brain use past experience as predictions of the immediate future? How can the human brain create many kinds of human minds? These more neutral questions have forced a paradigm shift in the science of mind and brain and led to innovative theories on emotional intelligence, parenting, and the roots of mental illness.

Everybody, please repeat after me: Cortisol is not a stress hormone. The amygdala is not the brain’s fear center. Neurons don’t light up and switch off. Maybe with some luck, we can put to rest these major folk tales about our gray matter. The brain is fascinating without them.

Lisa Feldman Barrett, PhD, is a University Distinguished Professor of Psychology at Northeastern University, with appointments at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital in Psychiatry and Radiology. She received an NIH Director’s Pioneer Award for her research on emotion in the brain, and most recently the 2018 APS Mentor Award For Lifetime Achievement. "How Emotions are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain" is her first book.