Evicted Roma in Plekhanovo, Russia, after a local court ruled in favour of destroying their illegally constructed houses. Tula Oblast, April 2016. (c) Andrei Varenkov / RIA Novosti. All rights reserved.Roma have long been reviled as a stubbornly marginal people, steadfast in their purported refusal to assimilate and assume the duties of modern citizenship. Likewise, Roma have been scorned, pitied, and rejected by modern nation-states as a people without a homeland. In the twentieth century, Nazi genocide resulted in the murder of an estimated one quarter of Europe’s approximately one million Roma. Today, the so-called “Roma question” in Europe continues to be framed as the need to solve the “problem” of Roma themselves; too few policymakers instead seek to solve the structural and socio-cultural inequities that have marginalised Roma for generations.

European policymakers have repeatedly denied Roma a claim to rightful belonging, evicting Roma from their villages, cities, and nation-states. In 2013, one French official shamelessly insisted that Romani migrants needed to “return to their homeland.” Persistent anti-Roma attitudes in Europe continue to negatively impact the lives of Roma in the form of racist violence, denial of education, exclusion from jobs, and other human rights abuses.

The “Roma question” in Europe continues to be framed as the need to solve the “problem” of Roma themselves

Studying Roma’s varied histories in Europe helps us to understand the roots of today’s so-called “Roma question.” It can also help us to appreciate historical alternatives. The history of Roma in the early Soviet Union, for example, highlights a governmental approach geared toward Roma’s integration as equal citizens. In the 1930s there was even a Stalinist attempt to fashion a Soviet homeland for Roma, who were known in Soviet parlance as Gypsies. Hundreds of Romani citizens themselves lobbied Moscow for a Soviet Gypsy homeland as a key to their integration into Soviet economic, social, and cultural life. None of this was idle talk. In 1936, the chairman of the Soviet of Nationalities celebrated the anticipated creation of an Autonomous Gypsy Soviet Socialist Republic.

The Soviet Union never did create an Autonomous Gypsy Soviet Socialist Republic. Nor did it offer Roma an autonomous Gypsy region – a lesser, yet still significant territorial prize from the grab bag of Soviet administrative options for ethnic minorities. Yet the little known history of the Soviet Gypsy homeland that never was reveals much about early Soviet approaches to managing the USSR’s ethnic diversity and to integrating Roma.

As such, it presents a vision of Romani civic belonging and homeland far different from those one typically encounters in Europe’s past and present.

Forging nations

The Bolsheviks sought to refashion life on earth. First, however, they had to begin by refashioning life on Soviet territory. Poverty, geopolitical isolation, and the harsh realities of needing to build a socialist economy from rubble were just a few of the challenges that dogged the Bolsheviks in their pursuit of socialist modernity.

There was also the related challenge of transforming a population that the Bolsheviks regarded as profoundly culturally backward. As a prerequisite of achieving socialist modernity, the USSR’s “backward” population needed to be transformed into New Soviet Men and Women who, by definition, would be literate, healthy, cultured, and dedicated to building socialism.

From the Bolshevik perspective, the bulk of the USSR’s ethnic minorities complicated this vision considerably. This is because the Bolsheviks regarded the vast majority of the USSR’s ethnic minorities as grievously arrested on the back end of the Marxist timeline of historic development. Oppressed by the tsars who exploited them in the interests of ethnic Russian advancement, the non-Russian peoples of the USSR would need special guidance and extra resources from the Soviet state in order to accelerate their path to socialist modernity.

Roma people in the Soviet Union, late 1920s. Photo courtesy of the author and the State Archive of the Russian Federation.It was in this spirit that the Bolsheviks crafted their nationality policy, summed up in the slogan: “national in form, socialist in content.” Roma and their fellow so-called “backward” ethnic minorities were entitled under this policy to Soviet forms of modern nationhood: national literatures, theaters, schools, and territories.

Suffused with socialist content, these national forms would accustom ethnic minorities to the Soviet way of life. In this way, a national theater, no less than a national territory carved into Soviet administrative space, would enable minority citizens to advance culturally. In other words, nationhood within the supranational Soviet state would serve to integrate Roma and other minority citizens into Soviet culture and the socialist economy.

Red Roma

The 1926 Soviet census counted a Soviet Roma population of 61, 234 – data then recognised as incomplete owing to the inability to accurately account for nomadic Roma. Despite their relatively small population, Roma occupied an outsized place in the Soviet imagination. In Bolshevik eyes, Roma jeopardised socialist modernity as a peculiar ethnic menace. According to a prevailing racist logic that assumed Gypsies to be universally illiterate, peculiarly nomadic, stubbornly marginal, socially parasitic, thieving, diseased, and superstitious, Roma threatened to jeopardise all of the Soviet Union’s modernising goals.

Of all the supposedly defining features of Roma, it was their purported nomadism that most perplexed Soviet modernisers. Theirs was, in the eyes of Soviet officialdom, a uniquely subversive, irrational, and unruly nomadism. In the Soviet bureaucratic imagination, labor-averse Gypsies wandered aimlessly and anarchically throughout Soviet territory. They escaped the state’s gaze, but also its demand that “backward Gypsies” become New Soviet Men and Women who contributed labor to the socialist economy. Gypsies were stereotyped not merely as peripatetics, but also as parasites who produced nothing of economic value.

In Bolshevik eyes, Roma jeopardised socialist modernity as a peculiar ethnic menace. Not only did they wander – they wandered aimlessly

Soviet officials responsible for solving the “problem” of Romani nomadism were intimidated by the seeming enormity of the task. Yet nationality policy provided them with a ready-made solution: give the “backward Gypsies” a territory on which they could settle and undertake productive agricultural life. The “national form” of territory would impose the “socialist content” of sedentary, socialist agriculture and the everyday life of Soviet cultural values. Ideally, territorialisation would mean sedentarisation as well as economic and cultural integration. In this way, “backward Gypsies” would become New Soviet Gypsies.

Early Soviet efforts to sedentarise and productivise presumed Romani nomads began with efforts to settle them on collective farms.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, as many as fifty Romani collective farms were established across the Soviet expanse. The rare successful farms among them were those established by sedentary Roma whose families had been farming for generations – whose sedentary life began long before the Bolsheviks endeavored to violently transform agriculture, let alone to settle Romani nomads. While many of the Romani collective farms collapsed almost as quickly as they had been created, hundreds of formerly nomadic Romani families found themselves, by 1933, settled on characteristically ramshackle collective farms that were scattered from Ukraine to Siberia, from the North Caucasus to Central Asia.

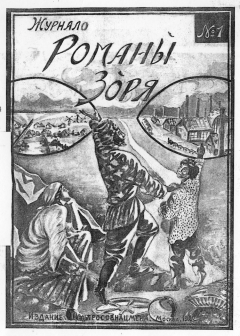

Romani Zorya (Romani Dawn), was a Romani-language publication launched in 1927. It aimed to showcase the achievements of Soviet Roma, and their transformation into model proletarians. Photo courtesy of the author.

Although generally regarded by bureaucrats in Moscow as failures, these collective farms were already showing some signs of success. Namely, the Romani collective farms were integrating their inhabitants into the lamentable agricultural sector of the socialist economy and Soviet culture.

Romani collective farmers learned quickly that nationality policy was a potentially productive framework for making claims on the state. They mastered the logic of nationality policy and soon began making fluent pleas to Moscow – begging for more state resources and invoking their own ascribed ethnic backwardness.

Romani collective farmers began – alongside urban Romani activists – to lobby for the establishment of a special Gypsy territory within the Soviet Union.

Only a Soviet Gypsy homeland, they argued, would enable the successful transformation of “backward Gypsies” into New Soviet Gypsies.

Roma’s lobbying for a Soviet Gypsy homeland fatefully coincided with the Soviet attempt to establish an ersatz Zion for Soviet Jews. Known as Birobidzhan and formally established in 1934, the Soviet Union’s remote Jewish Autonomous Region offered Roma a possible template upon which to base their own autonomous Gypsy territory within the Soviet Union.

Yet state efforts to create a Soviet Gypsy homeland also resulted from a renewed bureaucratic focus on battling nomadism throughout the Soviet Union. Officials within the Commissariat of Agriculture and the Soviet of Nationalities began, in 1935, to collaborate in crafting plans to establish an autonomous Gypsy region where, it was believed, the possibilities of rationally expending resources on the transformation of the USSR’s nomadic Roma population could be most effectively realised. A special commission was established to scope out suitable territory within the USSR to be transfigured into an autonomous Gypsy region.

The commission reached out to colleagues in a diverse array of Soviet regions to inquire about the suitability of establishing an autonomous Gypsy region within their administrative borders. Notably, they received positive responses from officials in the Gorkovsky (now Nizhny Novgorod) Region and in Western Siberia. Exploratory expeditions to these regions and bureaucratic reports soon followed.

Roma soon began making pleas to Moscow in a language it could understand – begging for more state resources and invoking their own ascribed ethnic backwardness

For a brief moment in the winter of 1935-1936, it seemed the Gypsy autonomous region might transition from the imaginative space of bureaucratic paper and Romani lobbyists’ petitions to the literal space of Soviet territory. In January 1936, the chairman of the Soviet of Nationalities exuberantly hailed a Soviet future that included a Gypsy Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. This Gypsy ASSR, he argued, would be the definitive answer to integrating Romani nomads into Soviet culture and the socialist economy.

In the spring of 1936, however, plans for an autonomous Gypsy region were scrapped. They were replaced with the decision to refocus bureaucratic energy and resources toward the strengthening and expansion of Romani collective farms.

Roma national territory within the Soviet Union would continue to be realized in the smaller forms of scattered and impoverished collective farms.

The Soviet Gypsy homeland that never was

The archives of the former Soviet Union reveal more than the dream of a Soviet Gypsy homeland that was embraced by a significant number of Roma and bureaucrats alike in the 1930s. They also testify to why that dream was abandoned. Soviet officialdom decided that it would be far too expensive to create from scratch a Gypsy homeland from underpopulated forest territories that were not the well-suited for agriculture and for a people regarded – through the prism of pernicious stereotypes – as ill-suited for sedentary agricultural life.

It is also clear how the fates of Jews and Roma converged in 1936 to help quash plans for a Soviet Gypsy homeland. Almost as soon as it was created, Birobidzhan was widely regarded in Soviet bureaucratic circles as an epic failure afforded at an astronomical price. Similar stereotypes, too, tethered the fates of Jews and Roma. Like Roma, Jews appeared in Soviet bureaucratic and popular imaginations as a scattered people with a perceived aversion to “honest labour” and especially to agriculture. Soviet officials confronting Roma’s pleas for a Soviet Gypsy homeland in 1936 were no doubt chastened by Birobidzhan’s depressing yet instructive example of a grandiose modernizing vision dissolving into the mud of inhospitable, even if Soviet, terrain.

That said, the little known history of the Soviet Gypsy homeland that never was has more to offer us than a reflection on Stalinist roads not taken. Soviet officials could easily scrap their embryonic plans for an autonomous Gypsy region not only because they imagined Roma in stereotypical terms that squared well with a dismal accounting of the ill-fated project’s cost-effectiveness. They could also easily scrap those plans because it was never a question that Roma already had a homeland: the Soviet Union itself.

The Soviet Union not only welcomed Romani citizens’ civic inclusion, it also demanded it

For all its failures, Bolshevik nationality policy represents in at least one crucial way a welcome alternative to the more well-known modern European approaches to Romani populations. Past and present, Roma throughout Europe have suffered profoundly at the hands of European states intent on fulfilling a variety of racist, exclusionary, and/or genocidal logics. The Soviet Union not only welcomed Romani citizens’ civic inclusion, it also demanded it.

The history of Roma in the early Soviet Union is a complex one. Yet it is overwhelmingly a history of how the Soviet state demanded that Roma participate in the economic, social, political, and cultural life of their multiethnic socialist homeland. Moreover, it is a history of how Soviet nationality policy – despite its limitations – provided Roma a framework through which to meet the demands of Soviet citizenship.

Although the dream of a Soviet Gypsy homeland was foreclosed, the Soviet Union insisted that its Romani citizens already had a homeland: the USSR itself.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.