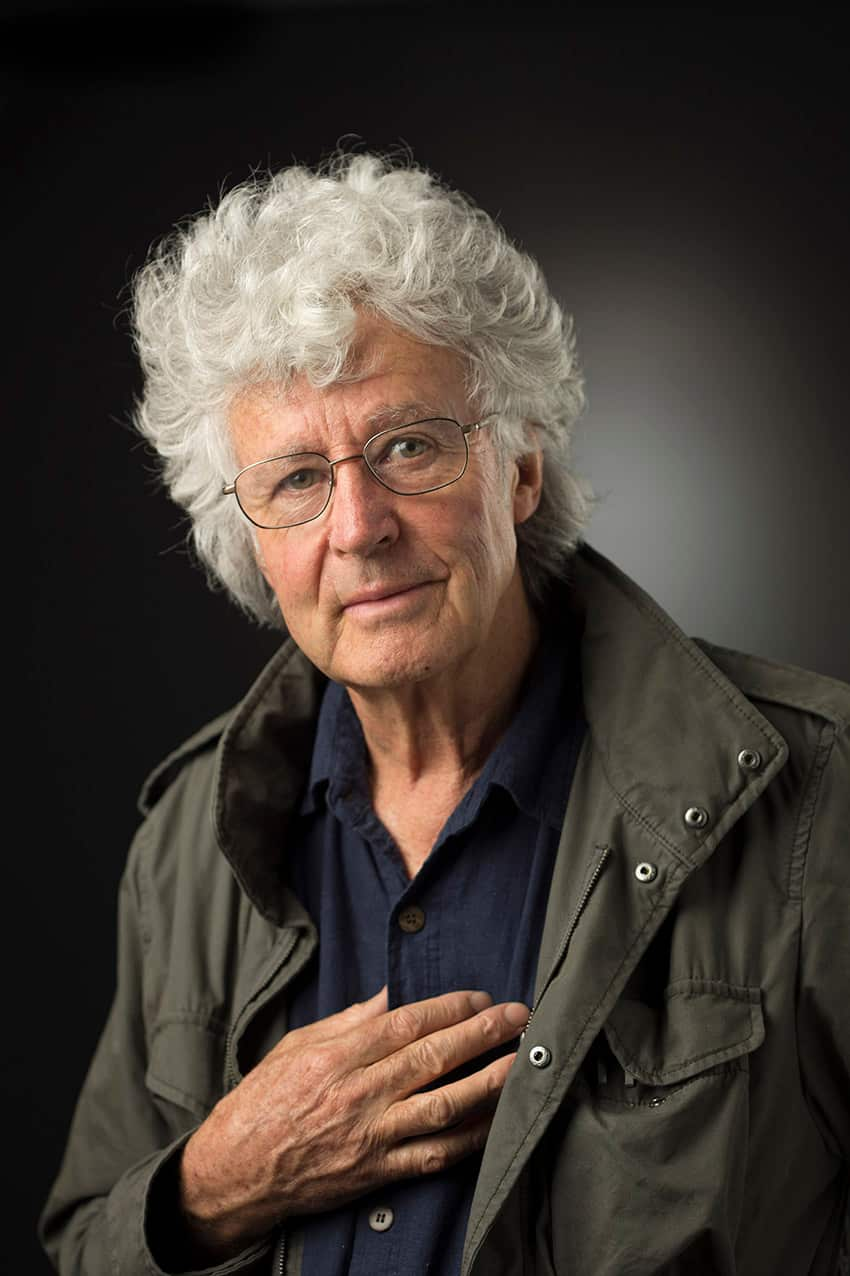

Michael Leunig avoids over-stimulation. The legendary cartoonist, artist and poet, who was named a National Living Treasure by the National Trust in 1999, builds his life around everyday pleasures: long walks, time in nature, conversations with people in the street.

“I try to keep a calm life,” Leunig tells SBS. “I don’t watch films or travel very much. It’s pretty unremarkable and I enjoy that. To me, the world seems more manic than ever, more desperate and consumerist and I try to avoid that sort of thing. That’s why I try as much as possible to have a steady routine.”

Leunig’s commitment to an ascetic and reflective existence isn’t surprising given that he’s spent the last 40 years creating cartoons for the Fairfax newspapers that cut through the noise of contemporary life. His drawings — philosophical, profound and often darkly witty — are designed to be pinned up, torn out, revisited when you’re mulling over a problem, the type that calls for something deeper than textbook obsession.

I try to keep a calm life. I don’t watch films or travel very much. It’s pretty unremarkable and I enjoy that.

Ducks for Dark Times, a new collection of cartoons (his twentieth in a series) is medicine for our cultural moment, taking on everything from the horror of the 24-hour news cycle and the numbing effects of technology to new age spirituality and the dark side of patriotism. Leunig says that the book, which features beloved characters like Duck and Mr Curly, is an extension of his lifelong artistic mission — giving voice to our existential concerns.

“I’ve always been interested in what motivates human beings and what they privately feel, deep down, which often happens to be universal,” he says.

“These things occur in the ancient texts of many cultures, in the poetry of the Sufis or the Hindus or the Buddhists. My concerns are eternal — they’re about what it’s like to be a lone soul on this earth, about our relationship to nature and to society. It’s about ‘who am I, what do I feel and what does that other person feel?’

“These things aren’t covered in the newspapers but they’re important to a lot of people but they don’t have the vocabulary. The artist’s work is to express what is repressed. We can repress our grief but we can also repress our joy.”

“I’ve always been interested in what motivates human beings and what they privately feel, deep down, which often happens to be universal.” (Photo by Sam Cooper) Source: Sam Cooper

The man behind the art

Leunig grew up in Footscray, Melbourne in the 1950s, the son of a slaughterman. Although his early influences include The Beatles, J.D Salinger and Martin Sharp, his upbringing was ordinary.

“I was part of a very working-class culture and it was Australia in the 1950s! There were no arts festivals, no awareness of artists,” says Leunig, who developed his political consciousness when he received a military conscription notice from the government in 1965 and started cartooning for The Age’s evening newspaper in 1969.

“But there were always comic strips and little comic magazines that I was drawn to. I wasn’t taught to draw, I learned to draw by copying. It was really the ideal way to start an artistic life in a sense, because anything was possible.”

Our minds are located in our body but it’s in our hearts as well.

Over four decades of editorial cartooning, Leunig has witnessed the ebb and flow of modern history from the Vietnam War, to the War on Terror to Trumpism. But the artist, who’s spent the last 18 months recovering from an accident which seen him relocate temporarily from the bush in Northern Victoria to Melbourne (“I’m very attached to the bush. I grieve for it!”) says that the bone-deep pleasure of putting pencil to paper has sustained him his entire life.

“There’s a great subtlety to drawing, the physical, organic act of it is so free,” he says. “Pre-schoolers often create works of great beauty but then they go to school and are told that they can’t draw. Why does a child draw so freely? And might we all be better off if we had places we could sit and draw? I think that we live in very cerebral and technological world and we’re removed from nature and increasingly from our own true nature. Our minds are located in our body but it’s in our hearts as well.”

is due for public release on October 30 and is published by Penguin Books Australia.