A quiet hysteria buzzed through Hiroshima in the summer of 1945. The Americans had been firebombing Japan for weeks, and it was one of only two key cities they had not yet hit. B-29 Superfortresses were stationed north-east of Hiroshima and had been flying ominously overhead – locals called these planes B-san or Mr B. “The frequency of the warnings and the continued abstinence of Mr B with respect to Hiroshima had made its citizens jittery,” wrote the New Yorker’s John Hersey. “A rumour was going around that the Americans were saving something special for the city.”

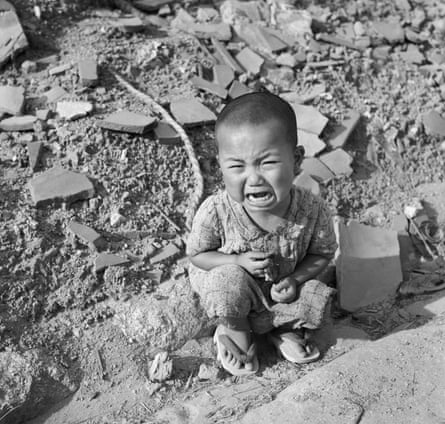

And then it came. At 8.15am on 6 August, Little Boy was dropped over Hiroshima. More than 100,000 people died, instantly or in the atomic bomb’s aftermath. “Such clouds had risen that there was a sort of twilight around … The day grew darker and darker,” Hersey wrote. A different sort of darkness would linger in Hiroshima.

Western press reports on the attack mainly covered the gruesome statistics; missing were the stories of the survivors. That autumn, New Yorker editor William Shawn decided the magazine had to cover the story. “He wants to wake people up and says we are the people with a chance to do it, and probably the only people to do it,” Harold Ross, the magazine’s founder, wrote to EB White. In May 1946 they sent the war correspondent John Hersey, who was in Shanghai, to see what he would find.

The result was Hiroshima, a 30,000-word piece published in a single issue in August 1946 and later reprinted as a book. Over the years, it has been recommended to me several times, often by other writers, as a canonical example of New Journalism. I duly added it to my list of books to read, but another title always seemed to make its way to the top of the pile beside my bed. In 2015, however, I received a slender edition of Hiroshima, released by Penguin on the 70th anniversary of the attack. When I look back on a year of reading, it is this book I would recommend without hesitation to anyone saddened and distressed by news from Paris, Beirut, San Bernardino, Syria. The subject is utterly, horribly contemporary.

Hersey tells the intertwined stories of six people in Hiroshima in the hours and weeks after the attack: a young surgeon; a pastor; a tailor’s widow with three children; a prosperous doctor; a female clerk at a tin factory; and a German priest. Its tick-tock approach gives it a Law and Order quality, as it switches its focus between the six subjects. But it is so much more: a chronicle of life amid the wreckage, with nary a word of hyperbole – a book that seems, at the close of 2015, more relevant than ever. It never promises an explanation for war, it never preaches. It eschews statistics in favour of story.

In fact, Hersey’s writing is so straightforward as to seem plain, but he often uses just the right word, or a simple but exquisite phrase, or a shattering detail, and his sentences are unmediated by a writerly presence. In one chapter, the pastor Mr Tanimoto was looking for a boat that would help him ferry the gravely injured across the river to safety. He came upon a punt on the shore. “It was an awful tableau – five dead men, nearly naked, badly burned, who must have expired more or less all at once, for they were in attitudes which suggested that they had been working together to push the boat down into the river.” Mr Tanimoto knew what he must do: he dutifully pulled the bodies away from the boat, but was so disturbed by “preventing them, he momentarily felt, from going on their ghostly way – that he said out loud, ‘Please forgive me for taking this boat. I must use it for others, who are alive.’”

Hiroshima is stitched together with many moments like this. Early on, we meet the tailor’s widow shortly after the mysterious explosion: “As Mrs Nakamura stood watching her neighbour, everything flashed whiter than any white she had ever seen … the reflex of a mother set her in motion towards her children. She had taken a single step … when something picked her up and she seemed to fly into the next room, over the raised sleeping platform, pursued by parts of her house.” (The family survived.)

Hersey’s documentary eye captures a full spectrum of feeling – panic, grief, disgust, resilience, hope – often on the same page. The German Jesuit Father Kleinsorge is at Asano Park, on the outskirts of the city, climbing over dead bodies to fill a teapot with fresh water, which he will offer to survivors. Coming back, he finds a group of 20 injured soldiers: “Their faces were wholly burned, their eye sockets were hollow, the fluid from their melted eyes had run down their cheeks.” With a flash of ingenuity, he makes a straw from a piece of grass so the men, whose mouths are swollen and covered in pus and who will probably not live out the night, can drink.

“Since that day, Father Kleinsorge has thought back to how queasy he had once been at the sight of pain … Yet in the park he was so benumbed that immediately after leaving this horrible sight he stopped on a path by one of the pools and discussed with a lightly wounded man whether it would be safe to eat the fat, two-foot carp that floated dead on the surface of the water. They decided, after some consideration, that it would be unwise.”

Hiroshima is filled with evidence of humanity at its worst and best, with stories of generosity, grief and pain. I was sickened by some descriptions, while others were surprising, like when the priests discovered that the pumpkins at the mission had roasted on the vine and made a tasty dinner. I also found myself disheartened that the book had little sense of resolution.

In the months after the attack, Japanese people tried to make sense of what had happened. Some were angry, some detached: “It was a war and we had to expect it,” many said. Others were philosophical: “The crux of the matter is whether total war in its present form is justifiable, even when it serves a just purpose. Does it not have material and spiritual evil as its consequences, which far exceed whatever good might result? When will our moralists give us a clear answer to this question?”

Hersey doesn’t attempt one himself and, notably, he closes with a young boy describing life after the atomic bomb. The boy seems remarkably well adjusted, so much so that it suggests the message that life goes on, that children will grow up and they will get by – one I found difficult to accept, perhaps because I realised that, 70 years later, not much has changed.

In this way, Hiroshima doesn’t seem like a history lesson. It is a raw, very human account of the death, destruction and resilience that, all these decades later, we still witness around the world. And it is also, as Harold Ross put it in 1946, “one hell of a story”.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion