The tremendously satisfying thing about Manolo Blahnik, the man, is that he is exactly the way you picture him. The singleminded fashion obsessiveness of Anna Wintour is spiked with the belle-epoque-bonkersness of Ab Fab's Patsy and housed in the body of Hercule Poirot. He is all lush formality and exaggerated polish – a bit like his shoes – both in his clothes (double-breasted suits, bow ties) and his manners. He insists on addressing me as Mrs Cartner-Morley, pronounced with the flourishes of a Spanish accent that has become quirkier rather than softer after 40 years in Britain.

Blahnik is this year's recipient – and we are exclusively announcing this today, by the way, ta-dah! – of the outstanding achievement gong at the British Fashion Awards. Manolo, who will be one day shy of his 70th birthday when he collects his trophy at the Savoy on 27 November, is already a Commander of the British Empire (awarded in 2007). And – better than any trophy – he has been a household name ever since Carrie Bradshaw pleaded with a Manhattan mugger: "You can take my Fendi baguette, you can take my ring and my watch, but please don't take my Manolo Blahniks." And yet the man himself, who today is on the phone to me from Italy, where he is visiting one of his factories, insists he "has no perception of success or failure. I keep looking ahead and thinking about challenges, because that's what keeps me going. If I look back I feel frightened, not happy, because my life is a bit of a mystery to me."

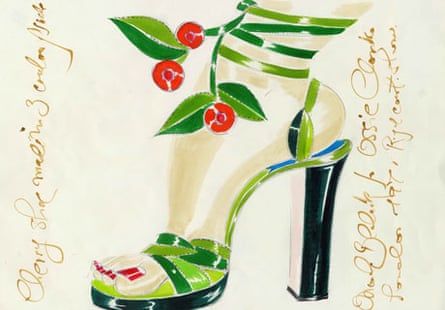

Actually, I know what he means. It is strange to think, now, that there was a time not so long ago when shoes were just shoes, rather than the magical totems of success and femininity they have become. Expensive high heels have become a motif in our popular culture for Stuff Women Want. They are how Olympians reward themselves for success, and the default shorthand of every chick-lit book cover. And the origin of this idea of the shoe as a magical object stems, in large part, from the way Manolo designs them. His sketches of shoes are extraordinary: not inanimate line-drawings but character portraits, sensual and suggestive. Richard Avedon's fashion photography showed us how clothes can lend charisma and attitude to the wearer, by teasing out and emphasising the posture and silhouette of the body. Manolo did the same with footwear. With his sketches, Manolo has done more to open the eyes of the world to the transformative power of the right shoe than anyone since Cinderella.

And yet, Manolo has never really cashed in on the phenomenon he helped create. He has never sold his company. He still personally designs every pair of shoes that bears his name, rather than delegate to a studio. Key roles in the company are held by members of his family, and he has never done a lucrative mass-market collaboration, along the lines of Jimmy Choo for H&M. He is a wealthy man with an enviable lifestyle, but perhaps not as wildly rich as one might expect. He lives in Bath, in an 18th-century townhouse that he adores; he says he moved there in the 1980s because he "could not possibly afford" such a house in London. "But who cares? I couldn't care less about business," he says cheerfully.

Manolo was born in Santa Cruz de la Palma in the Canary Islands in 1942, to a Czech father and a Spanish mother living comfortably on a banana plantation. He paints an idyllic picture of his childhood. "My mother was exquisite. She was born on an island so she was untouched by the outside world, but she had what I call a natural, given taste. And she loved English books, and read to us every night – Oliver Twist, Little Dorrit, Enid Blyton. My father always had on Radio Casablanca, wonderful Arab music, and the maids would sing the Andalucian popular songs. Englishness, and also Spanish and African influences, all of which remain important to me today."

In his late teens he was sent to study in Geneva, where (brilliantly incongruous image) he spent a summer interning at the United Nations. He escaped, via Paris, arriving in London in 1968, and immediately fell in love with England – particularly the England of that era, names from which (Cecil Beaton, David Bailey, Anjelica Huston) stud his conversation like cloves in an orange, lending colour to a modern world one senses he feels is drab by comparison. Prompted by Diana Vreeland, then editor of American Vogue, who spotted sketches of an ankle entwined by ivy and cherries in a portfolio of fashion and set-design sketches, he began making shoes. By 1971, he was collaborating with Ossie Clark; by 1973, he was getting raves in Womenswear Daily.

He learned the craft of shoemaking by painstaking study in the best manufacturing studios. I remind him of something he once said, that he didn't need formal training because he had such good taste. "Oh, what pretentious things one says! I hope I was young! But actually, I do have taste. And it is important."

Just as a delicate stiletto conceals a cylinder of steel, there is an inner stubbornness to Manolo. He has never modified his aesthetic, creating shoes with a slender sole even when the prevailing fashion is for a vast platform. "I hate platforms," he says flatly. "The young girl who is a bit chubby, or whatever, she thinks platforms make her look taller. But no, they just make her look weird." This singularity of vision has meant that the brand drifts in and out of fashion, but for the past few years it has been on a high. (Consider: when Kate Moss got married, she wore Manolos.) He also invests a great effort in making sure his shoes are comfortable, and spends around three months of each year visiting his factories. "I love exaggerated, and I love eccentric, but you must be comfortable. Otherwise it is nonsense. There is nothing charming about a woman who cannot walk in her shoes."

Who does he think looks charming, I ask – meaning, in my shallow way, which celebrities. "Do you know who I think looks wonderful? In Bath, there is a woman who always passes by my house. She wears twinsets, and usually a tweed pleated skirt. Not terribly expensive but good quality, and she always looks just perfect. To me, that's fabulous."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion