Hughes Glomar Explorer

When the CIA went looking for a lost Russian sub, it built a one-of-a-kind ship for the job

09/23/2018

When a Soviet ballistic missile submarine sank in the northern Pacific in 1968, it set off an audacious and expensive recovery plan by the CIA, the likes of which had never been seen before. At the center of this plan was a unique ship, the Hughes Glomar Explorer, designed and purpose-built for the deep-sea operation and shrouded in a cover story that the spies almost got away with.

When the Golf-II-class K-129 disappeared somewhere between the Kamchatka Peninsula and Hawaii, the Soviet Navy mustered more than three dozen ships in a frantic search, to no avail. The U.S. Navy, however, with its advanced underwater listening system and a specially equipped submarine, was able to pinpoint its exact location under 16,000 feet of water.

Armed with this information, defense and intelligence officials convinced President Richard Nixon to authorize the clandestine recovery of K-129, its nuclear weapons, code books and other secrets--a potential treasure trove. Tasked to the CIA, this operation was given the code name "Project Azorian." Intelligence officials contracted Global Marine, Inc., a world-renowned oil-drilling outfit with deep-sea experience, to design and build a vessel that could undertake this Herculean task.

Built by the Sun Shipbuilding and Drydock Company in Chester, Pennsylvania, the Hughes Glomar Explorer was 619 feet long and 116 feet wide--too fat to fit through the Panama Canal. It also had what amounted to a floating drydock in its hull, with the center section of the underside opening like doors to store the submarine once it was lifted off the ocean floor. Sun equipped it with bow and stern thrusters, guided by satellite navigation, to keep the ship stationary over the recovery site during operations. With its distinctive tall steel lattice towers, it bore some resemblance to other drilling ships. It was launched in 1972.

Other contractors on the West Coast handled other aspects of the estimated $350 million project. The actual recovery device, a massive eight-clawed grapple named Clementine, weighed over 2,000 tons. In order to secretly load Clementine into the HGE's hull, a 300-foot covered, submersible barge was built. After sailing around Cape Horn, the Glomar Explorer loaded Clementine from below in broad daylight in the shallow waters of Catalina Island, off the coast from Los Angeles.

One problem with building such a large, unique and expensive ship is that people start asking questions. Though Howard Hughes had nothing to do with Project Azorian's operations, he gave his name and helped with the propaganda, his company insisting that the Hughes Glomar Explorer was headed to the Pacific to begin mining the mineral-rich ocean floor. Between press releases and industrial films, the cover story was so convincing that other mining companies began exploring the possibilities and the U.N. even wanted an international agreement defining ocean-floor mining rights.

The Glomar Explorer arrived on site on July 4, 1974, and stayed for more than a month. Though part of the K-129 broke apart as it was being raised to the surface, a fair amount of the submarine was recovered; the exact details remain classified. A chance break-in at Hughes' Los Angeles offices in 1975 had the CIA and the FBI on the scene investigating. The appearance of the feds alerted reporters and the story of Project Azorian became front-page news. Still, when approached by reporters, the CIA, for the first of many times, offered its "We can neither confirm nor deny" response, an action now referred to as a "Glomar denial" or "Glomarization."

There's an old saying in the automobile business: You never want to be too far behind styling trends, or too far ahead. Finding that sweet spot between styling that’s too conservative and too advanced is critical, and the Mitchell automobile is a good example of what can happen when a design is too far ahead of trends.

In 1919 the Mitchell Motor Company of Racine, Wisconsin, was considered a veteran automaker. It had begun producing motorcars in 1903, one year after Rambler and the same year as Ford Motor Company. Mitchell was profitable, a picture of success and prosperity, yet five years later the company was out of business and its plant sold to another carmaker. It proved a cautionary tale for other automobile companies.

Courtesy of Pat Foster

One of the first products of the Mitchell Motor Car Company was the small runabout seen here. Although the photo is identified as a 1903 model it appears to be of later vintage, possibly 1904/1905.

The Mitchell saga began in 1838 when Scottish immigrant Henry Mitchell moved to Kenosha, Wisconsin, and established the Mitchell Wagon Company, a manufacturer that became known as "The first wagon maker of the Northwest." Successful almost from the start, in 1854 Mitchell moved his business to larger quarters in nearby Racine. It continued to expand and in time son-in-law William Lewis joined the company. Lewis eventually headed the firm and changed its name to Mitchell & Lewis Wagon Company. During the Gay Nineties, Mitchell & Lewis established another business, the Wisconsin Wheel Works, to produce bicycles, and for a while was manufacturing light motorcycles too. Thus,established in the transportation field, the idea of producing automobiles was the next logical step.

In a major change of company direction, Wisconsin Wheel Works sold its bicycle business and was succeeded by the Mitchell Motor Car Company, a subsidiary of the Mitchell-Lewis Wagon Company. The former’s first models were two small runabouts: one powered by a 7-hp, single-cylinder two-stroke engine, the other by a 4-hp, four-stroke single. Reportedly, sales were modest, despite prices that began at a mere $600 for the 4-hp model. It seems the company initially had difficulty reaching high-volume production due to problems acquiring sufficient parts and components, but when resolved sales quickly improved.

For 1904 a new 7-hp two-cylinder runabout on a 72-inch wheelbase chassis, and a 16-hp four-cylinder touring model on a 90-inch wheelbase, replaced the previous one-lungers. The two-passenger runabout was priced at $750, while the five-passenger touring car started at $1,500.

Courtesy of Pat Foster

Mitchell’s 1910 cars were priced from $1,100 to $2,000. The company said of its car, “It is rakish, smart, refined, solid, comfortable and luxurious. It is silent in running – absolutely silent – and it will last and serve you faithfully for years to come.”

In the years that followed Mitchell cars grew bigger and more powerful. In 1906 a 24/30-hp five-passenger, 100-inch wheelbase Model D-4 Touring car joined the expanded line-up priced at $1,800. The company reportedly sold 663 cars that year. For 1907 Mitchell offered three distinct series: the Model E, a 20-hp two-passenger Runabout on a 90-inch wheelbase; the Model D 24/30-hp five-passenger 100-inch wheelbase Touring; and the Model F seven-passenger Touring on a 108-inch wheelbase. Prices ranged from $1,000 to $2,000 and total sales more than doubled.

By 1910, Mitchell was offering five models: two- and three-passenger runabouts and a Runabout Surrey in the Model R series, each powered by a 30-hp four-cylinder engine and priced at $1,100; and two touring cars, a 30-hp four-cylinder Model T for $1,350, and a 50-hp six-cylinder Model S priced at a lofty $2,000. That year’s sales totaled 5,733 units. (There was even a jaunty little song titled "Give Me a Spin in Your Mitchell, Bill,” a recording of which can still be found on the internet.) The same year, Lewis retired, and Mitchell Motor Car Company and Mitchell & Lewis merged to form the Mitchell-Lewis Motor Company with Lewis’s son,William Mitchell Lewis, named president.

In 1912 a stylish $2,500 four-cylinder Limousine joined a line-up that included a budget-priced 25-hp Runabout for $950 and an $1,150 Touring car, both of which used a four-cylinder engine and a 100-inch wheelbase chassis. Also available was a $1,350 four-cylinder Touring, while a Model 5-6 34-hp Baby Six Touring and Roadster were available on a 125-inch wheelbase, each costing $1.750. Finally, there was a big seven-passenger Model 7-6 six-cylinder Touring on a regal 135-inch wheelbase for $2,250. Sales for the year were 5,145 cars.

Courtesy of Pat Foster

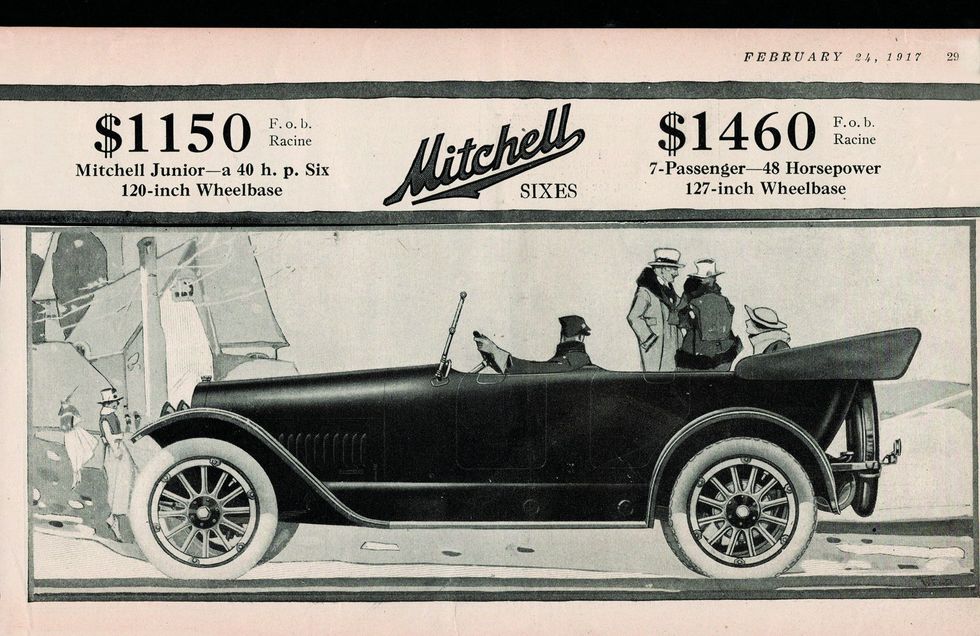

The Mitchell line of six-cylinder cars for 1917 saw lower prices, with the Mitchell seven-passenger priced at $1,460 and the Mitchell Junior priced at $1,150.

Unfortunately, sales were just 3,087 cars in 1913 and William M Lewis left the firm to start a new company building the so-called Lewis car. Banker Joseph Winterbottom took over as president and the firm was reorganized as the Mitchell Motors Company. Only 3,500 Mitchells were sold in 1914, perhaps a result of the company’s emphasis on higher-priced models. For 1915 new lower-priced Light Four and Light Six models seemed just the thing to spark a revival, and some 6,174 Mitchells were sold that year.

Mitchell sales manager Otis Friend then took over as president. Believing that offering more cylinders was the way to go, for 1916 the company dropped its four-cylinder models in favor of value-priced six- and eight-cylinder cars. It was the right move; sales climbed to 9,589 units, its highest total yet.

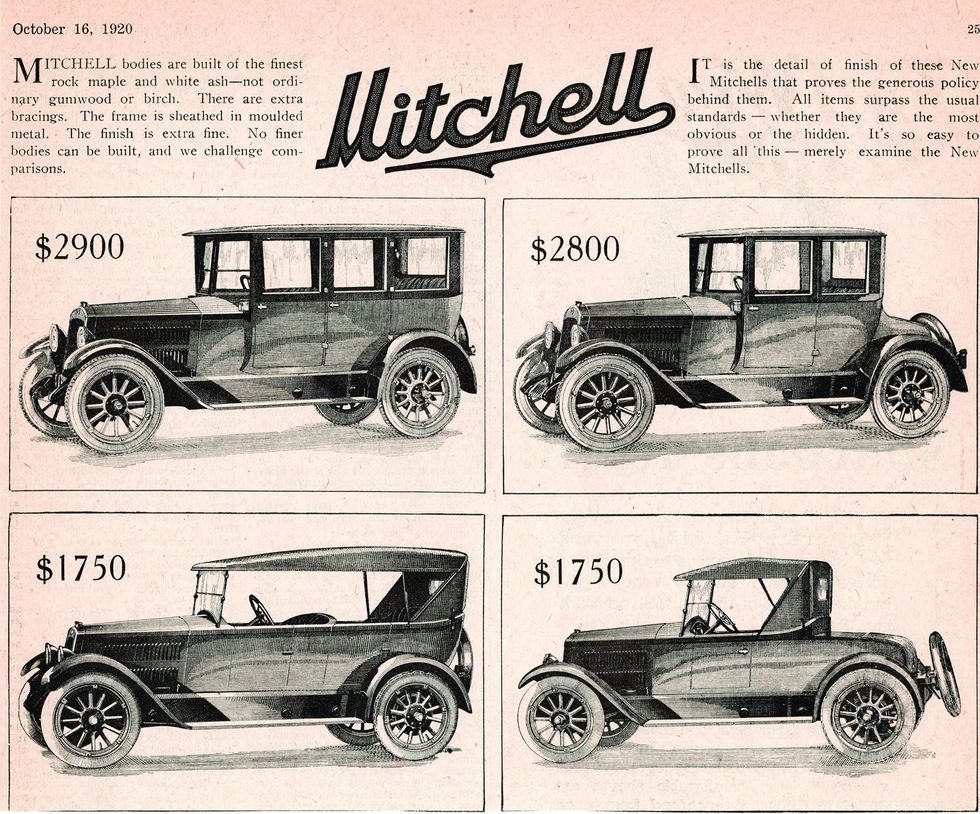

The company continued to flourish, selling 10,069 cars in 1917, but in ‘18 Otis Friend left to start his own car company in Pontiac, Michigan. Replacing him was formerGeneral Electric executive D.C. Durland. Things initially went well, and by 1919, Mitchell prices ranged from $1,275 to $2,850; some 10,100 cars were sold. While the company was profitable, it seems management might have been feeling over-confident because for ‘20 it was decided new Mitchells would feature unique styling touches to help them stand out.

Sedans boasted unusual vee'd windshields, with a prominent forward-placed center post supporting angled side panes, and cowls featured a forward sweep on each side, very much in the style of expensive custom-built cars. The angle of the sweep didn’t match the angle of the windshield post, which gave the closed cars a slightly odd appearance. The biggest styling feature, one that was impossible to ignore, was a radiator that tilted back at a noticeable angle. Print advertisements bragged that "Future styling trends…" were "Forecasted by the new Mitchell design." Ads claimed, "These new Mitchell Sixes bring to motoring America its first accurate example of the coming style [and].... viewed from any angle–from inside or out - the effect is impressive."

Courtesy of Pat Foster

The 1920 Mitchell Touring car, to my eyes, looks a bit sporty with its sweptback radiator shell, but many buyers didn’t like it.

Looking at the 1920 Mitchells today it’s difficult to see any big styling problem. In fact, on Touring models the sweptback radiator adds to the sporty appeal, at least in my opinion. But on closed cars the different lines and angles of the split vee-d windshield post, cowl sweeps, and radiator shell offer too much visual conflict. Apparently, they must have seemed even more at odds with convention then because the ’20 models soon earned the nickname “The Drunken Mitchells.”

Pundits love to poke fun, so "The Drunken Mitchell” sobriquet stuck. It’s easy to guess what happened next. Sales fell 36 percent, with the slump worsening in 1921 when a mere 2,162 cars were sold, this even after a hasty restyle. The ’22 model year was about the same. Then in 1923 Mitchell sales collapsed entirely and only about 100 cars were sold. The company had come to the end of the line. Despite a history going back more than 80 years, Mitchell was gone by the end of 1923.

One company benefitted from Mitchell’s demise. In January 1924, the Nash Motors Company of Kenosha, needing more production capacity, acquired the Mitchell plant for $405,000.

If there’s one thing we’ve learned about automotive barn finds, such discoveries are not always the cut-and-dry variety. You know, the classic image of some rarity being pulled from a structure so dilapidated any hint of wind might bring it crashing down. There are the well-used, truly original vehicles that have spent the static hours of existence in dusty, century-old abodes, handed from one family member to the next. Some barn finds were never really lost, rather just left to languish under the auspice of an idyllic restoration that never seems to happen. And then there are barn finds that have a habit of migrating home.

A case study is this 1964 Buick Riviera. It’s never really been lost, technically contradicting “find,” yet its decades-long dormancy in more than one storage facility, and with more than one owner, makes this first-gen GM E-body a prime barn find candidate. More so when the car’s known history, and relative desirability, can be recited with ease by current owner Tim Lynch.

Tim, a resident of West Deptford, New Jersey, is well versed in Buick’s Riviera legacy, thanks largely tohis dad, Gene Guarnere, who has had a penchant for the personal luxury car since he was a teen. “My dad has been into first generation Rivieras since he came home from Vietnam in 1967. That’s when he got his first ’64 to drive back and forth from South Philadelphia to Fort Dix, to finish his draft requirement,” Tim says.

Since then, Tim estimates his dad has owned too many Rivieras to count, through a combination of having driven, collected, parted out, and rebuilt many for resale. Though the Riviera nameplate lasted for eight generations of production, and thirty-six years as a standalone model, the 1963-’65 editions will always be Gene’s favorite. “There’s something about those Rivieras. There was really nothing like them on the market at the time,” Gene says.

The Riviera name had a long history with Buick. It first appeared in conjunction with the revolutionary true hardtop design unveiled within the 1949 Roadmaster lineup, the missing B-pillar ushering in “Riviera styling.” That design moniker evolved slightly through the mid-Fifties, provoking thoughts of elegant open road motoring for a modest price, and it even survived Buick’s model name revamp of ’59, when it became a trim level within the Electra 225 series though ’62.

Right about the time the dust was settling from the Buick renaming buzz, GM Advanced Styling guru Ned Nickles had already created a sketch of a new car that–according to later interviews with Nickles and GM Styling boss Bill Mitchell–was based on Mitchell’s foggy visit to London, where he spotted a custom-bodied Rolls-Royce in front of the Savoy hotel. Mitchell is famously quoted as saying, “make it a Ferrari-Rolls-Royce.”

Photo by Scotty Lachenauer

What makes this 1964 Buick Riviera desirable among collectors is the optional dual-quad 425-cu.in. V-8, which boasted 360 hp. It would become the foundation of Gran Sport option a year later.

Coincidentally, Cadillac was considering the introduction of a junior line to bolster sales, helping prompt the development of the XP-715 project (Mitchell is also quoted as saying GM didn’t take kindly to Ford attending the Motorama events to study concept cars, which lead to the four-seat Thunderbird, prompting development of the XP-715). Unofficially, it was dubbed La Salle II, but by the time a full-size clay mockup had been created, Cadillac had reversed its sales slump and was having trouble filling orders. It didn’t need a new car complicating matters.

The XP-715 might have been forgotten had Buick’s general manager Ed Rollert not learned of its unclaimed status. He made a pitch for the project but would have to fight for rights to it with Oldsmobile’s and Pontiac’s management. The latter was lukewarm on the idea of adding another series, while Olds wanted to modify the existing design, something Mitchell was deadset against. By April 1961, the XP-715 / La Salle II concept mockup was photographed wearing Buick emblems.

In the fall of 1962, Buick rolled out the Riviera on a new E-body platform. The car was a departure for Buick, with “knife edge” body lines, minimal trim, a Ferrari-like egg-crate style grille flanked by running lamps/signal indicators behind 1938-’39 inspired La Salle grilles, and kickups over the rear wheels designed to hint at the car’s power (helping conjure the “Coke bottle” design nomenclature). It was an amalgam of styles, fitting in somewhere between a sports car and luxury car, all rolled up in one breathtaking package.

Speaking of power, the Riviera was equipped with Buick’s four-barrel equipped 401-cu.in. V-8 that boasted 325 hp and 445 lb-ft. of torque, though in early December, the division started to offer the 340-hp, four-barrel 425-cu.in. engine as optional Riviera equipment. Just 2,601 examples of the latter were produced. Backing either engine Buick’s Twin Turbine Dynaflow automatic in its final year of production.

Photo by Scotty Lachenauer

Although the cabin is in dire need of detailing, it looks otherwise complete.

A year later, Buick management elevated the 340-hp, single four-barrel 425 engine to standard power team status, paired with a new Super Turbine 400 automatic transmission. Peppy as the engine was, a dual four-barrel version of the 425 became available, known as the “Super Wildcat.” Aside from its eye-opening 360 hp and 465 lb-ft. of torque, it looked the part of a performertoo, due to finned aluminum rocker covers and a twin-snorkel chrome air cleaner assembly. Despite its low production, only 2,122 of the 37,658 Rivieras built for ’64 came equipped as such, this engine became the cornerstone of Riviera’s Gran Sport package for ’65, cementing Buick’s legacy as a luxurious personal muscle car.

Although any first-gen Riviera is a great score to Tim and Gene, some examples are better than others, whether it was due to overall condition or the car’s born-with options. So, when this 1964 Riviera popped up on Gene’s radar 30-plus years ago, he quickly made a deal. “The history between my dad and this car is a long one. He first bought this car in northeast Philadelphia for $1,450 in the early Nineties,” Tim says.

The reason Gene wanted it more than any other that previously crossed his path was that not only was it in reasonably good shape, but the Buick also turned out to be one of the relatively rare dual-quad 425 examples. But like many of the Rivieras that came Gene’s way over the years, the Buick didn’t stick around too long. “The car was sold and/or traded multiple times for the first fifteen years my dad knew about it,” Tim says.

However, like all good things, they somehow find their way home and this car is no exception. “For some reason, the Riviera always ended up with us some way or another. I finally ended up buying the car from the last owner in 2009. He had it stored in my dad’s barn during his ownership, so we knew it was in a safe place for a long time. I now have it tucked away in one of my garages waiting for the next phase in its lifeline.”

What Tim has in possession is an interesting example beyond the power team. “This Riviera is typical of the examples built in ’64. It’s just chock full of options that cater to the upscale buyers that would have had the funds to purchase one of these high-end rides from the dealership.”

Present within are many of the accoutrements that catered to the posh consumers in the luxury sports car market. Options here include the Deluxe vinyl and cloth interior, tilt column, and power seats. Power windows and power vent windows add to the lavishness of the Buick’s aesthetic, while its front seat belts, rear armrests, wood ornamentation, and rear defroster only add to the upscale feel.

Though it's seen better days, the condition of the interior is remarkable, knowing of its lengthy journey since it was taken off the road circa 1980. The upholstery is dirty and moldy but with a good washing it will probably clean up nicely. The dash is also in great shape, though since the V-8 has not been started in years, there’s no way to determine what gauges and switches are functional. Underneath the carpet, the floors are solid as well, owing to its life mostly indoors.

Photo by Scotty Lachenauer

The 1938-'39 La Salle grille is said to have inspired the Riviera's vertically stacked running lamp grilles.

Under the hood it looks as if the engine has barely been touched. It’s “KX” code stamped on the block is still visible, the original Carter carburetors are present, and the wiring and plumbing still appear usable. The air conditioning looks to be intact as well. Finally, power brakes and power steering round out the luxury amenities.

Outside, the body is in excellent shape for a car of this vintage. The last 30-plus years of indoor storage has helped keep the metal intact, though minor body work will be needed on the quarter panels to get it up to snuff. The original Claret Mist paint has turned to a satin finish under all the dirt, but a good cleaning and buff could bring it back to life. Most of the trim is also in great shape, and the car appears to be relatively complete, save for a few pieces of rear window trim.

As for the mechanical functionality beyond instrumentations, no one is really sure of its condition “My first order of business would be to send the engine to “Nailhead” Matt Martin in California, who is an artist that works in the nailhead medium; he’s the ultimate authority in these V-8s. I believe the rest of the car deserves a nut and bolt restoration, too. That time will come soon,” Tim says.